The modifiers vs. the keepers

Throughout the history of keyboards, a battle has been fought by two opposing camps.

On one side, there were keyboards with the modifier keys – the Shifts, the Controls, the Commands. They appeared in QWERTY’s suburbia the moment typewriters needed uppercase and lowercase characters, and never went away.

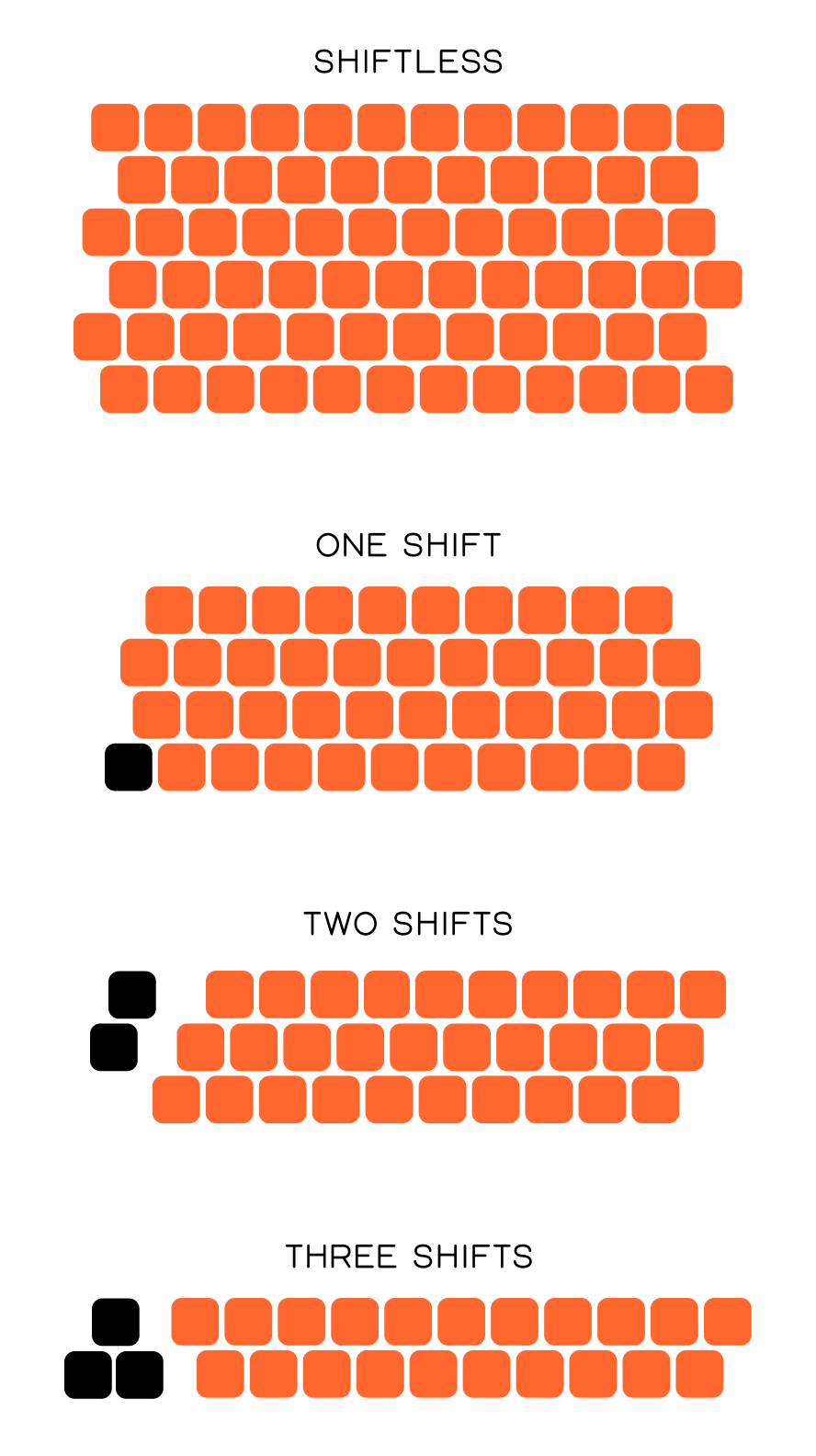

Early typewriters experimented with two, or even three separate shifts, and while eventually we standardized on just one Shift key (cloned onto both sides of the spacebar for convenience), other modifier keys followed in due time – Margin Release in typewriters, Ctrl in teletypes, Code in word processors, Alt in terminals. Each one added at least one new possible function to other keys, and likely more after you started combining the modifier keys (like in the infamous Ctrl+Alt+Del).

The other camp took a simpler, more obvious approach: You want more things to come out of your keyboard? You’re going to need more keys.

The movement started with now-forgotten, shiftless typewriters of the 1880s that put capital letters above or beside lowercase letters.

Specialized typesetting keyboards like Linotype or Monotype picked up the mantle – they, too, eschewed shifts and added even more specialized typographical characters.

When those machines befriended electricity first, and electronics later, the trend continued, with some keyboards reaching astonishing heights of hundreds of keys (we’ve talked about some of them a few years ago).

And when computers fully took over, some of those character keys became surrounded by dedicated command keys, still following the same rule: One key had only one job, ever, described precisely by its label.

These keyboards offered few surprises. The layout was, well, the keys to the kingdom, its own treasure map, its own instruction manual.

When some modifier key machines tried to explain themselves – most notably 1982’s ZX Spectrum – it became a confusing mess of multiple labels and colours per key. And believe it or not, ZX Spectrum, being a simple computer, had it easy. In other cases the wealth of functions made the task impossible. (This is often where keyboards resorted to using overlays and stickers, making the situation even more messy before explanations largely moved onscreen.)

But “keeper” keyboards – I’m calling them that after a nickname for an HP calculator that came from “a key per function” – were by their nature cleaner and easier to understand. What you saw printed on your keys was what you have gotten.

And so, the upside was obvious. But so was the downside.

⌘

We know that Word came for typewriters, pixellated calculator apps took over pocket calculators, and desktop publishing software like PageMaker eradicated huge and heavy Linotype and Monotype machines. But the story of software replacing hardware has lesser-known nooks and crannies.

In the early 1980s, a Dutch manufacturer released Aesthedes – a specialized computer for graphics and CAD applications. It was an early equivalent of something like Adobe Illustrator, AutoCAD, or (today) Figma.

And it was a beast.

Aesthedes had three big, full-colour screens – one for the current layer, one for all the layers, one showing a zoomed-in view – and three small ones to print out layer names and command history.

Underneath the screens was a digitizer (more or less a computer mouse in a business suit). And surrounding the digitizer were keys. Lots of keys.

This was the apotheosis of “a key per function” approach.

Many features you can recognize from the interfaces of modern graphics software are here: 64 keys to switch between sixty-four layers, a sophisticated colour wheel, visual boolean operations, moving, mirroring.

Many sections have their own red Enter keys, and you realize that this keyboard is so big it enters the realm of information architecture – the various islands of keys are nothing more than a graphical user interface, small dialog boxes realized in an unusual medium.

And yeah, there is a regular QWERTY keyboard here, too – for typing in and naming things – easy to miss in a sea of other keys. (The only modifier keys on the whole keyboard can be found here.)

I counted 534 keys on the second revision of Aesthedes, and that was before realizing some of them were two keys in one enclosure, like the key to move an object left or right. Adding those half keys resulted in the machine with an astonishing 583 keys, laid out in front of the designer, occupying the space of an entire desk.

⌘

There is a reason you don’t see a lot of keeper keyboards today. The modifier key camp won the battle. Software ate the world, and one of its courses was specialized computers. A word processor key labeled Bold was replaced by a combination of ⌘ and B, special characters can now be had by holding ⌥ or Alt, and even some early universal computer keys like Scroll Lock or Insert are dropping off one by one. A lot of the key-based commands became onscreen menus and then graphical user interfaces. Eventually, smartphones blurred the lines between the keyboards and interfaces so much they became indistinguishable.

We might never again get a machine like Aesthedes, a 583-key graphic computer that was the final hurrah of the “key per function” camp. The machine was obsoleted by another computer released in the same year: the Apple Macintosh and its svelte, 58-key keyboard, bundled with the mouse that stole the show.

The Mac led to PageMaker, Illustrator, iPhone, and iPad. “What you see is what you get” was redefined to mean what was going on on the screen, not on the keyboard. The Aesthedes? It was a dead end.

Breaking historians’ hearts, specialized machines like Aesthedes are often the first to be thrown away. This is where the downsides rear their ugly head – the computers are simply too huge and too heavy to preserve. They also never get much of the benefit of nostalgia, and even if they do – I can imagine the designer of the Heineken logo or the Dutch bank notes harboring some fond memories of Aesthedes – they are usually owned (or leased) by a company. The Aesthedes system cost close to 100,000 pounds, a figure unattainable to individuals.

I came to terms with the fact that I will never get to use the PolType or the old Monotype machines. But my last week’s visit to The Netherlands came with a surprise. Miraculously, at least three copies of Aesthedes exist in three different computer museums – University of Amsterdam’s, Bonami SpelComputer Museum in Zwolle, and HomeComputerMuseum in Helmond. And even more miraculously, the last of these museums is making an effort to restore the machine to its working order.

It’s a tough task, and a curious reversal of a lot of restoration efforts: the keyboard lays out a lot of functionality bare, and it’s the schematics and the details of its innards that are missing. But the place is making progress.

During my visit, one of the volunteers told me he estimates the work at 95% complete. I responded with “can’t wait to see it run.” His answer surprised me. “We can see it run now,” he said, and powered the machine without much ceremony. I got to see Aesthedes boot, and, for a brief moment, actually use it.

I don’t have too many photos of those few minutes, too absorbed in trying to figure out the machine’s immense keyboard. (Seeing all the functions as keys didn’t automatically make us understand them!) Neither the volunteer nor I knew exactly how to operate the machine, and after creating a simple object, my desire to type in some text managed to freeze the entire system.

But it was a tantalizing moment, a promise of a non-too-distant future where you can watch someone operate this fascinating culmination of a design trend that no longer exists – or even perhaps operate one yourself, with supervision.

As we were talking, the volunteer asked cheekily: “You saw the keyboard, right?”

I responded with a blank expression on my face. After all, I just typed on the largest keyboard I knew to survive to 2022.

But he reached out to the front of the massive case, and pulled out a tray with… yet another keyboard. A keyboard we’d today call a “mechanical” one, ready to support more intense typing tasks.

The extra keyboard brought the total key count on the Aesthedes 2 to an absolutely incomprehensible 636 keys.

And it’s good to know these 636 keys, and the machine they’re attached to, will soon again get their time to shine.

Marcin

This was newsletter №28 for Shift happens, an upcoming book about keyboards. Read previous issues · Check out all the secret documents