New in the collection, pt. 2: NEC PWP-100

A small tidbit about Keyport 717 that caught my eye was people worrying about its memory requirements. If each key can output not just one, but more characters, and there are over 700 keys, that can quickly add up to a few kilobytes. In an era where your Apple II might have 16 or 32 kilobytes total, even two kilobytes becomes a noticeable tax.

In Japan around that time, this kind of challenge would be amplified manyfold – and it affected everyone, not just nerds wanting something like Keyport. Japanese writing system has thousands of characters, many of those characters couldn’t be rendered with enough precision on a 8×8 grid common in early microcomputers, and to input them you simply needed a keyboard with even more software assist than Keyport’s.

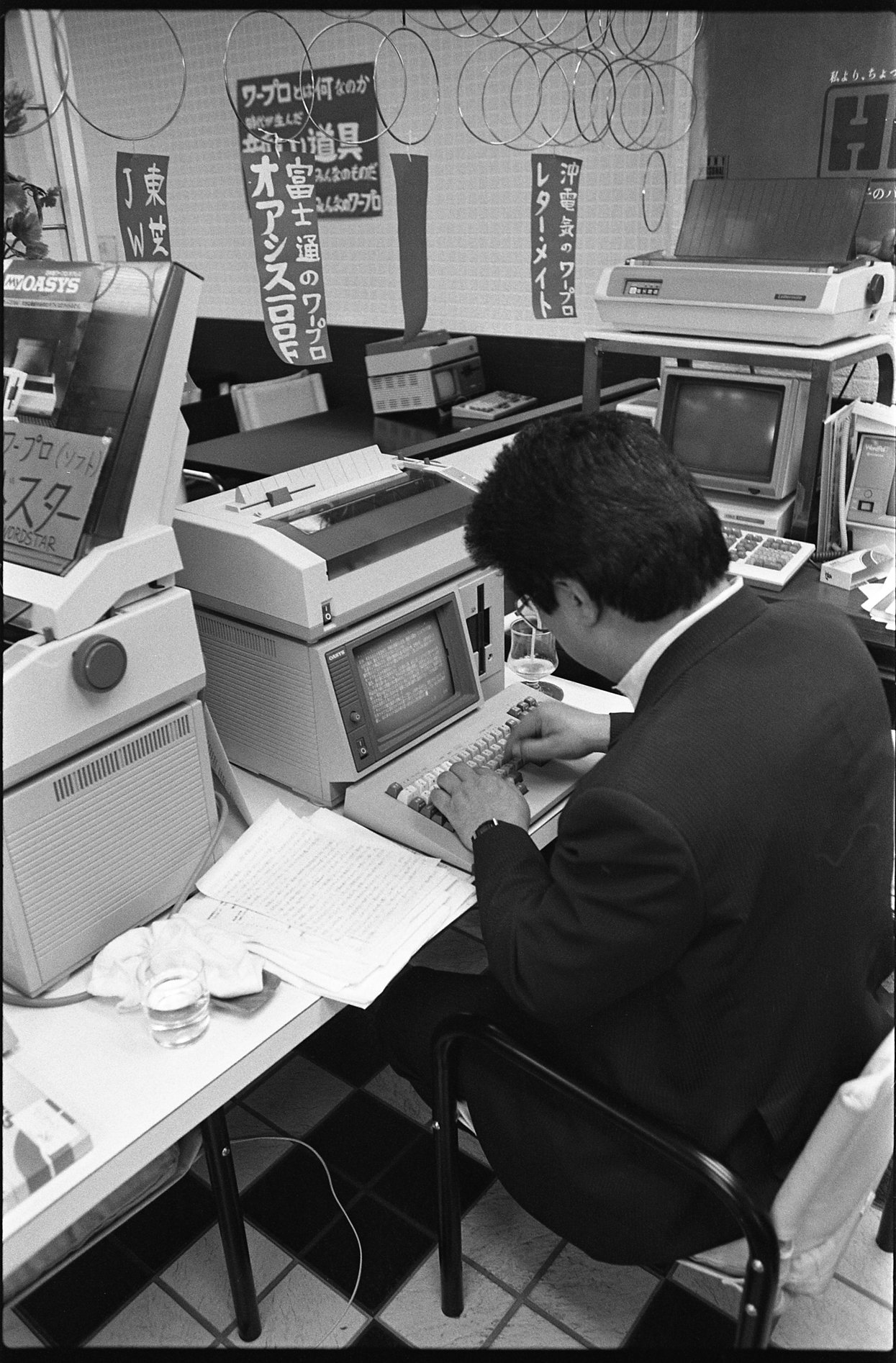

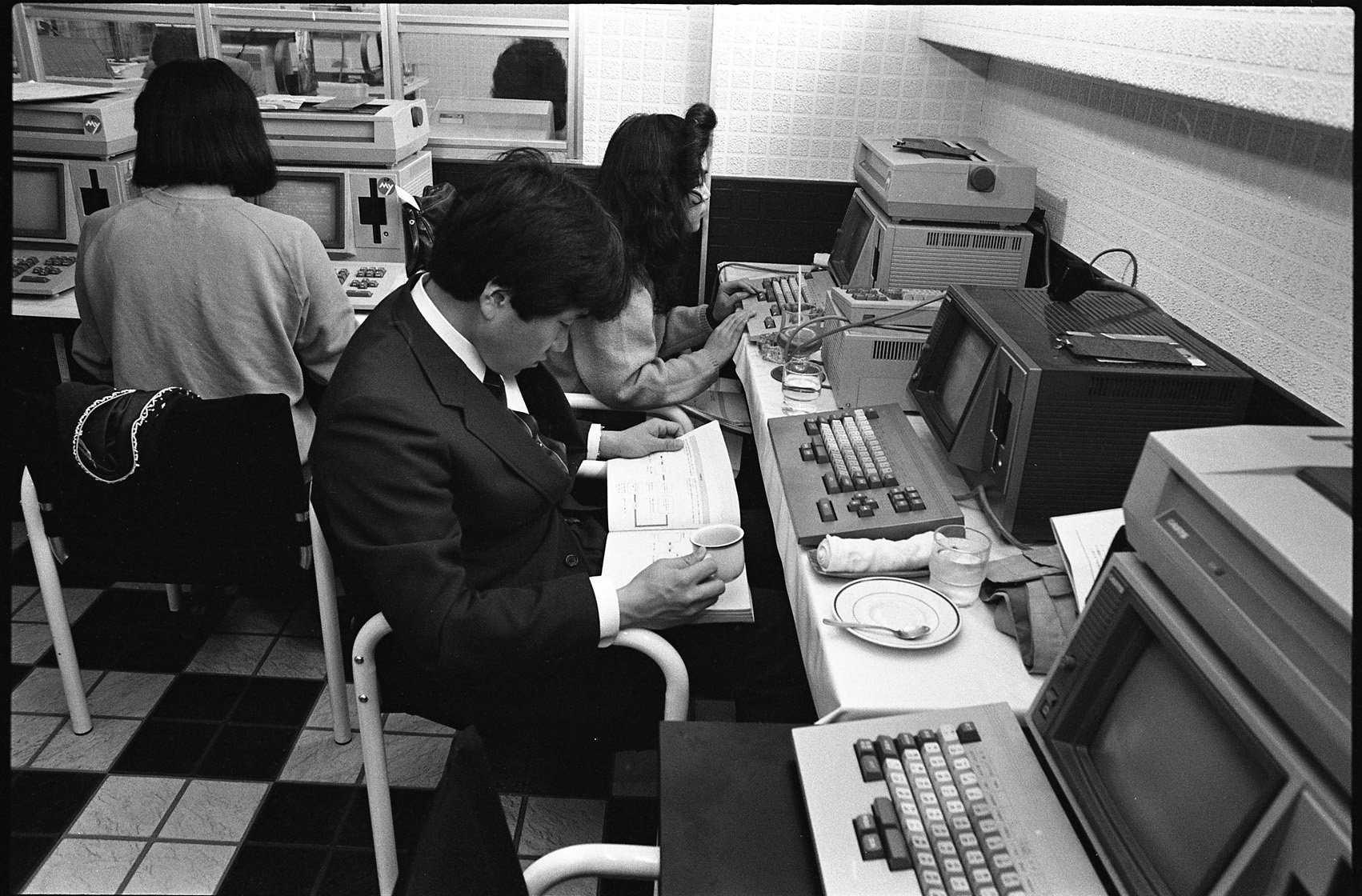

Writing in Japanese required more memory, more pixels, and more technology that doing it in English or most other languages – and memory, pixels, and technology became “more enough” only in the late 1980s. This explains why the path the writing technologies took in Japan feels so distinctive: completely different point-and-shoot typewriters (also often exported to China, which faced a similar problem), scant home and office typewriter adoption throughout the entire century, 1980s word processor machines unlike any other, and unique internet cafés that hosted them before they migrated into homes in the 1990s.

I tried to capture a snippet of it all in chapter 34; it truly was a parallel universe where layout battles and Shift Wars happened not in the decades closing off the 1800s, but one whole century later.

⌘

The jokes about Chinese and Japanese keyboards simply not existing as they would need infinite number of keys (I reprinted two in the book and I don’t think I need to do that again) were based not as much on the admiration for the complexity of the respective writing system, but on racist ridicule that those writing systems are primitive, cave-drawing-like, and not as evolved as alphabets elsewhere.

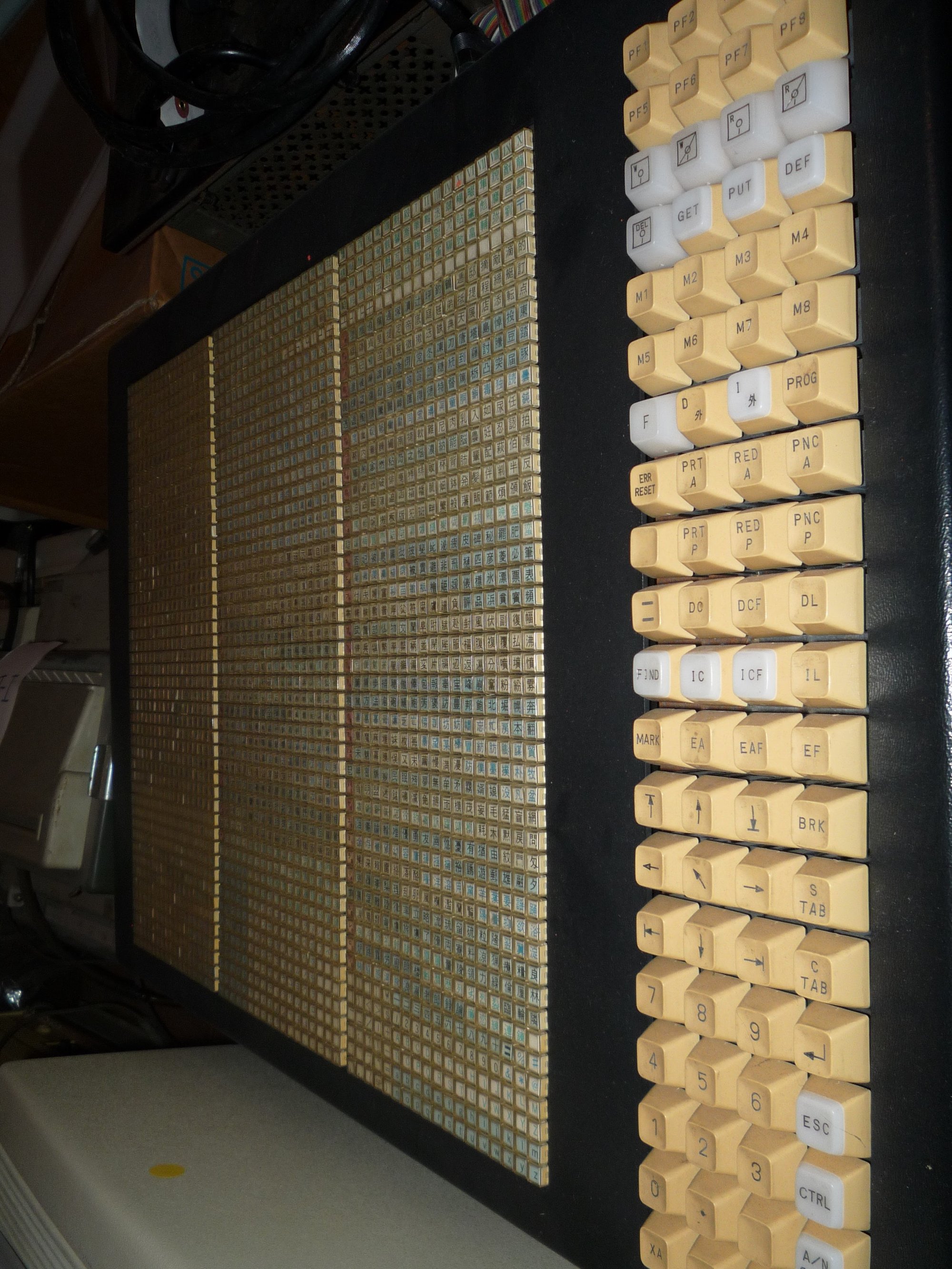

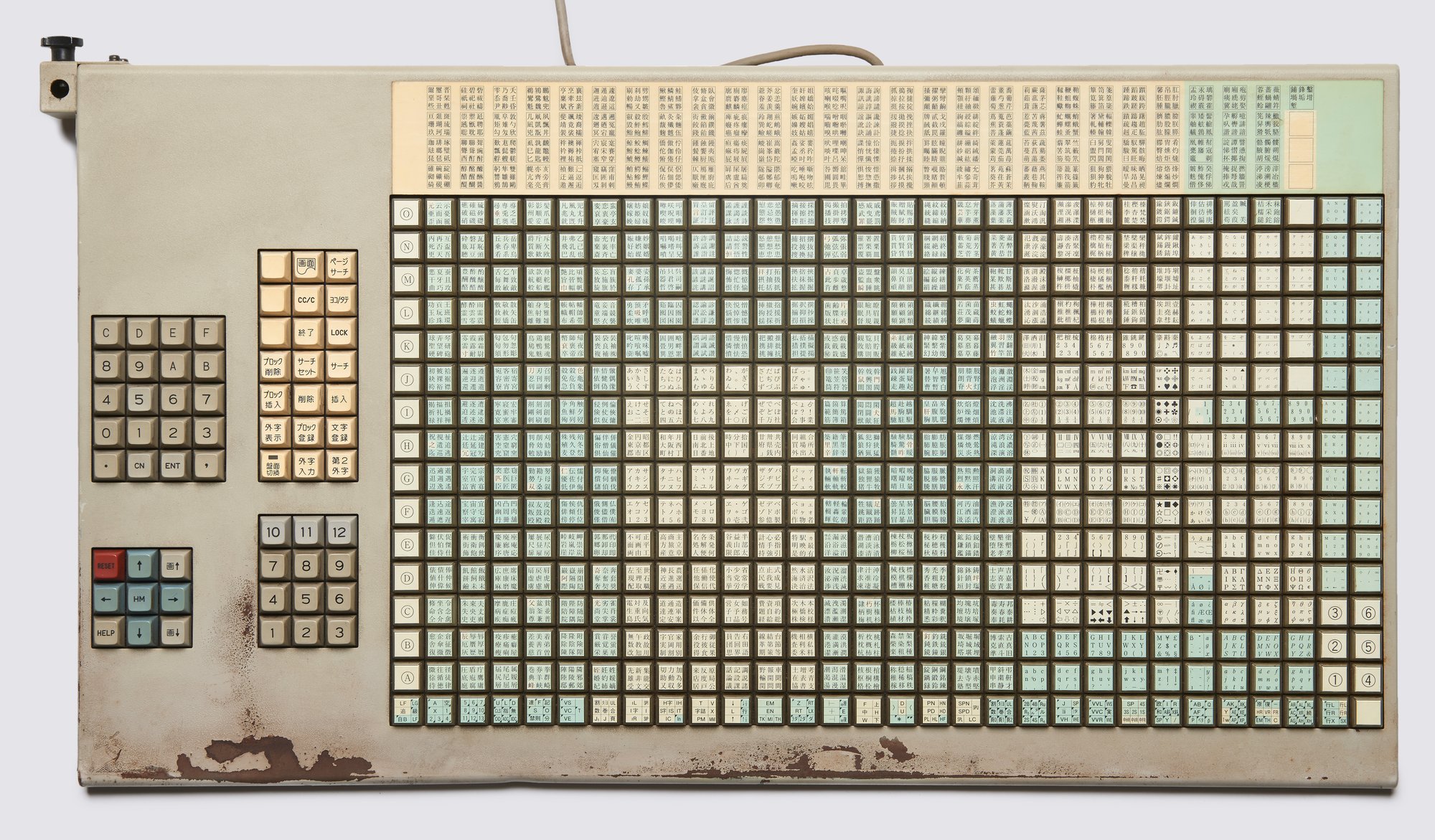

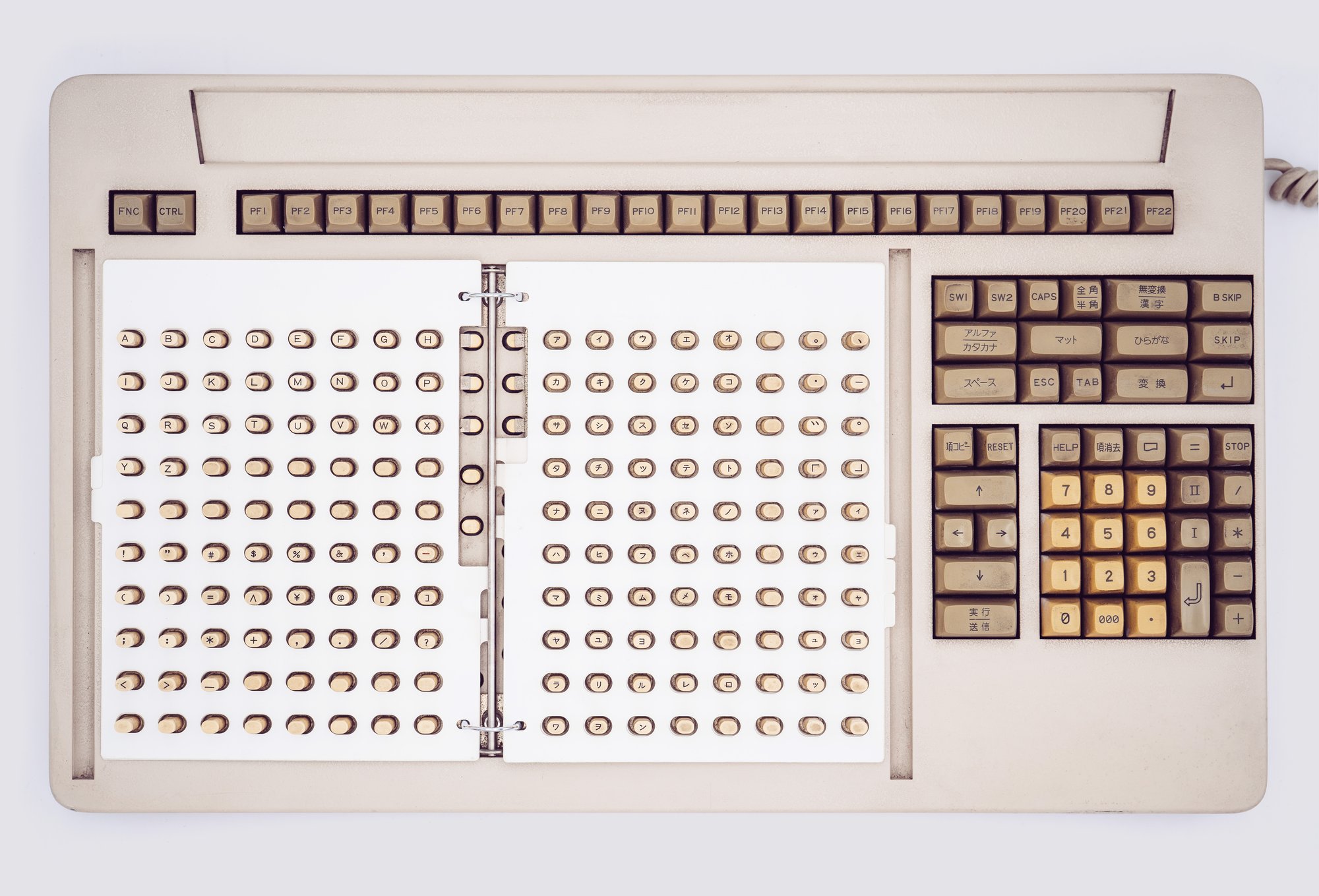

And there were some keyboards with thousands of keys. I don’t know much about them. Even the one I included in the book, and this extra photo I’m adding here, is from a keyboard I know for sure has since been destroyed (hence the word “extant” in the previous newsletter post).

If thousands keys are not your speed, Shifts are an answer – but introducing 12 of them still makes the remaining keys number in hundreds…

…so other keyboards tried various creative solutions with stylii, flipping pages, and other ideas…

…only to see designers eventually gravitate toward layouts that were QWERTY-like, where handling the Japanese writing system would be moved from hardware to software, where it was easier to hide complexity.

But even then those weren’t literally Western QWERTY: Fujitsu, for example, evolved their thumb-shift keyboards, and TRON came up with a fascinating splayed layout with two sets of arrow keys.

And this wasn’t all. Recently, I got a few keyboards that helped me flesh out this fascinating landscape.

⌘

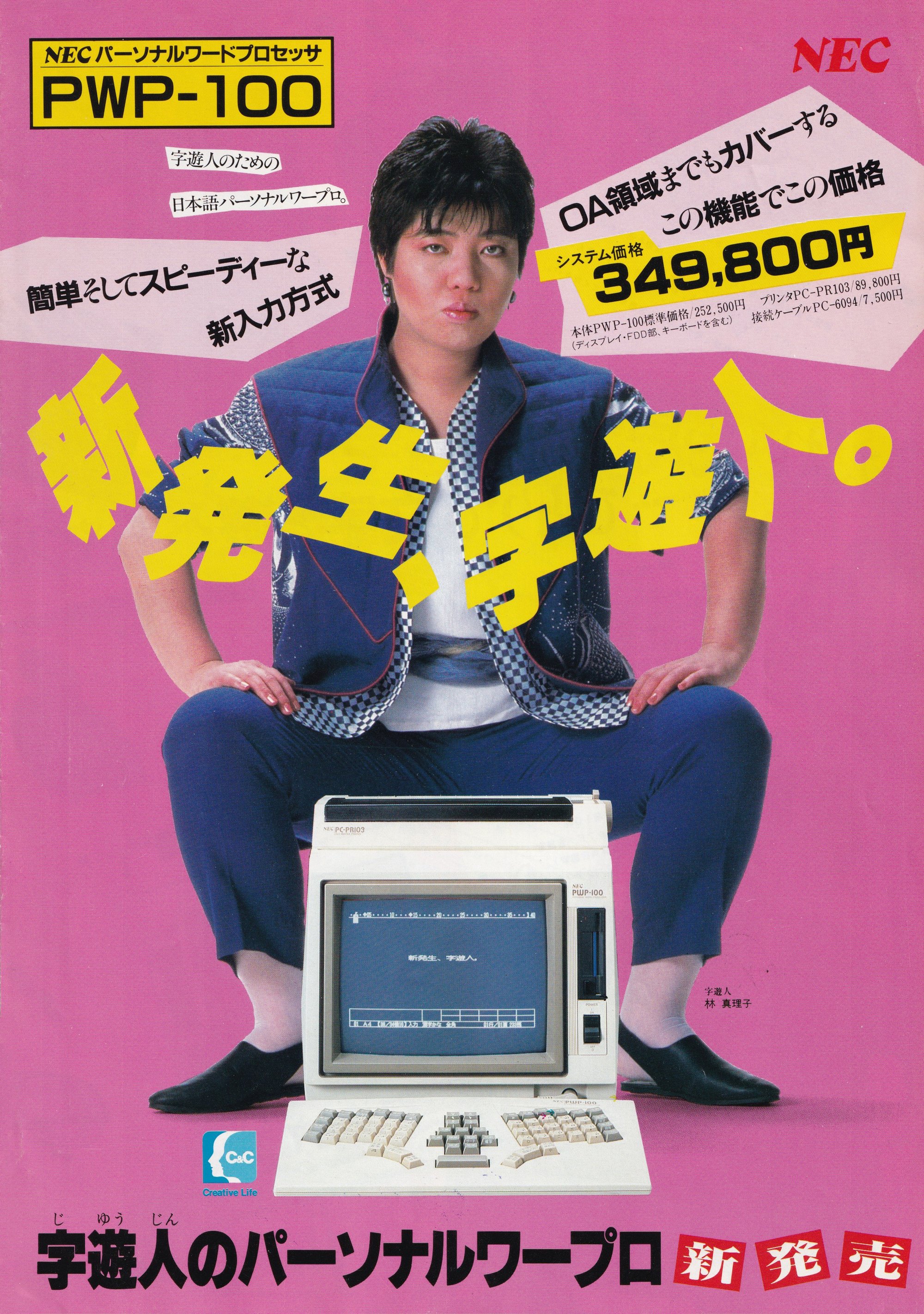

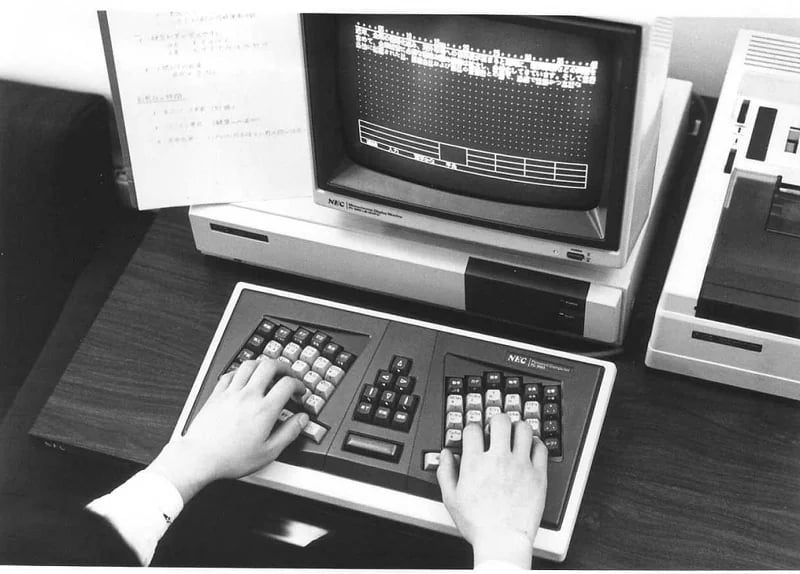

First is a NEC keyboard known either as PWP-100, or PC-8801-KI. (The first one is a “Personal Word Processor” variant, the other was available for NEC’s popular line of general-purpose computers.)

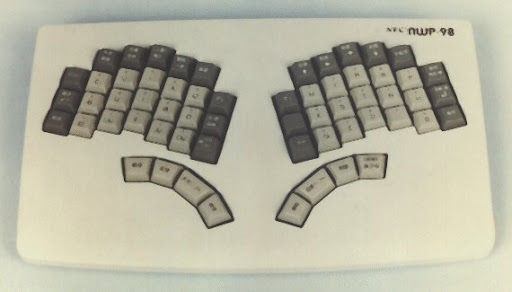

It’s just… it’s beautiful, isn’t it? Attractive in a kind of utilitarian way, with just the right balance between rigidity of machinery and flowing shapes of human bodies. Many other “ergonomic” keyboards aspired to this kind of simplicity. This is what Apple Adjustable secretly always wanted to be – symmetrical when other keyboards couldn’t be, ortholinear when that wasn’t yet popular, mixing rectangular and organic in all the right proportions.

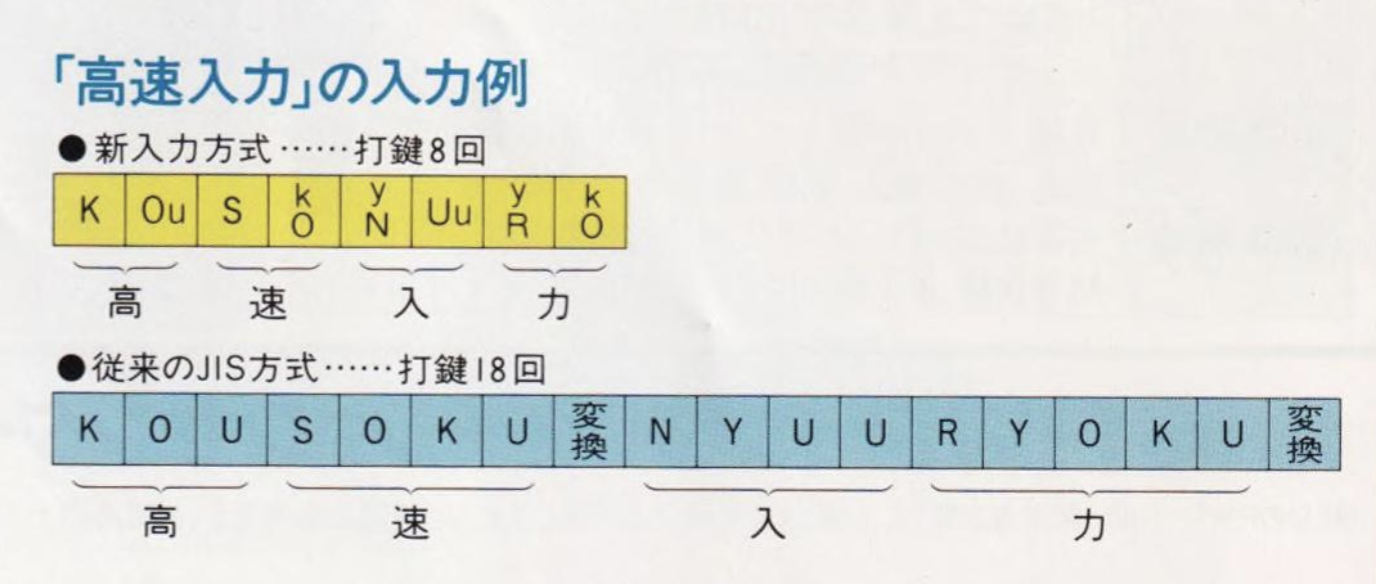

“This board looks like endgame material,” quipped a modern (Western) observer. I can’t vouch for its novel 68-key layout known as M system, although I feel both EUIAO under one hand, and the strangely arranged arrow keys would make August Dvorak proud.

Just like last time, I scanned the brochure if you want to check it out. It feels more 1990s than it ought to be, and boasts of “a new input method that fully understands the characteristics of the Japanese language.”

I wish I could tell you more about it; perhaps someone fluent in Japanese can weigh in. IPSJ Computer Museum has more of the details and thinking behind the keyboard, yet again reminding me of the explainers coming out in the late 19th century when first typewriters were justifying their layouts.

⌘

M keyboards survived well into the 1990s, but like all the other contenders, they succumbed to the boring QWERTY. However, as I wrote in my long-ago dispatch from Japan, they still managed to carve out a fascinating flavour of QWERTY with small quirks that persist until this day.

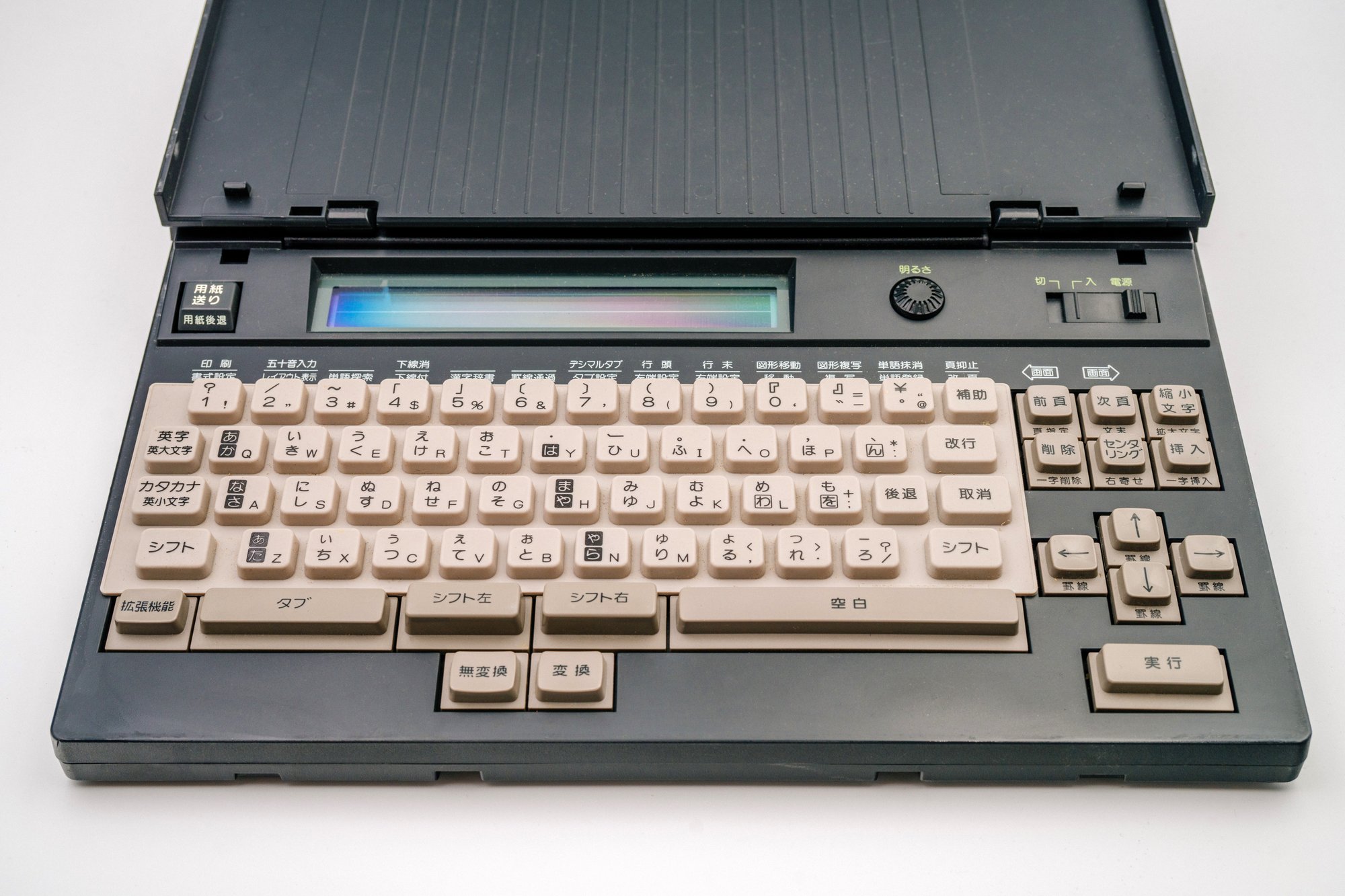

But coming back to NEC’s M system, I particularly like this version with dark case, and slightly different center layout:

There was an even more spartan version that felt incomplete…

…and I had less love for all the subsequent editions, murkier and uglier:

Sometimes the first take is the best.

⌘

It’s fun to look through Japanese computer magazines of that time and glimpse at a parallel universe – although despite Internet Archive’s experiments with in-line translation, it still too often feels like the true meaning of that era and its design decisions remains opaque.

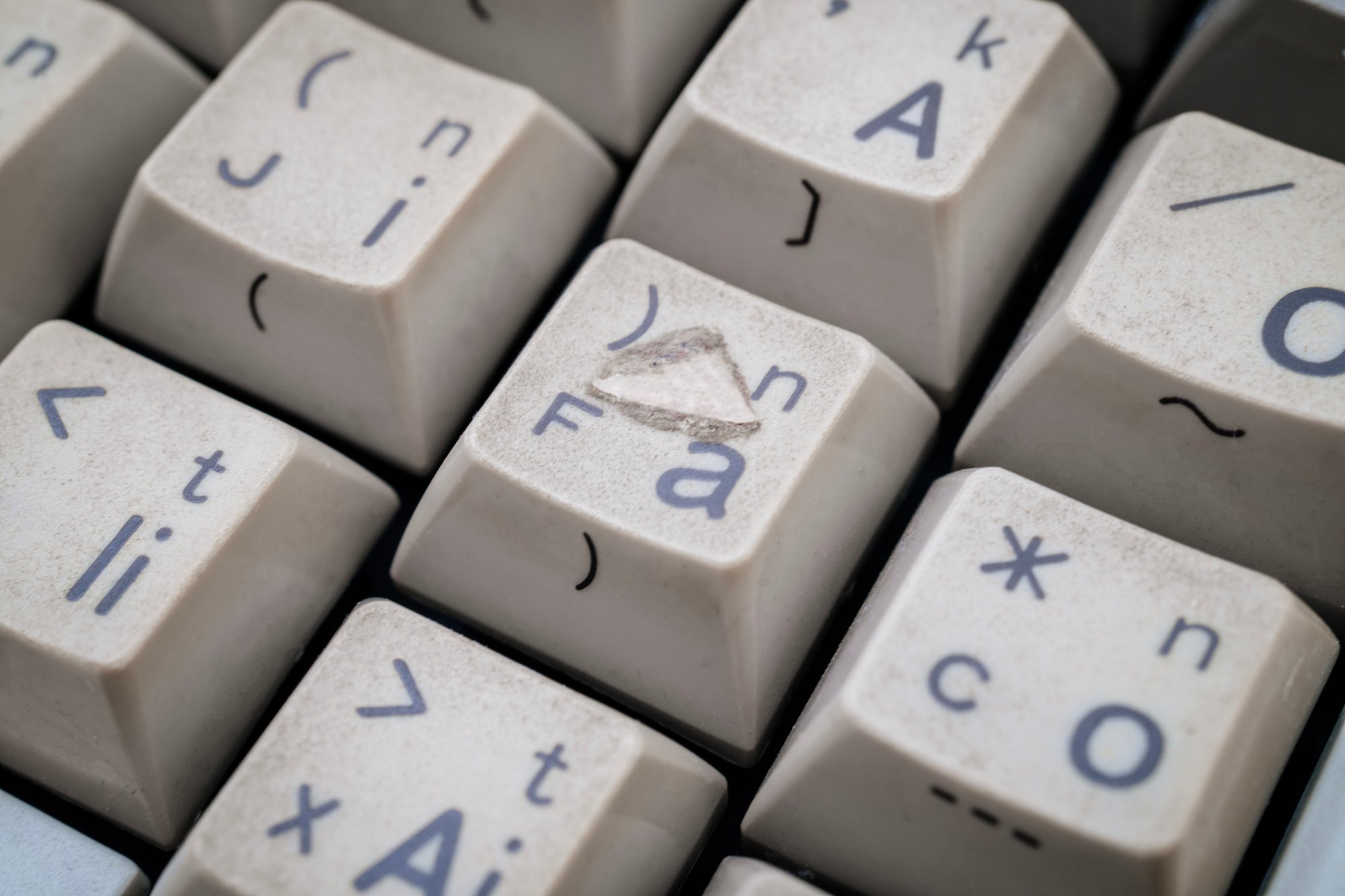

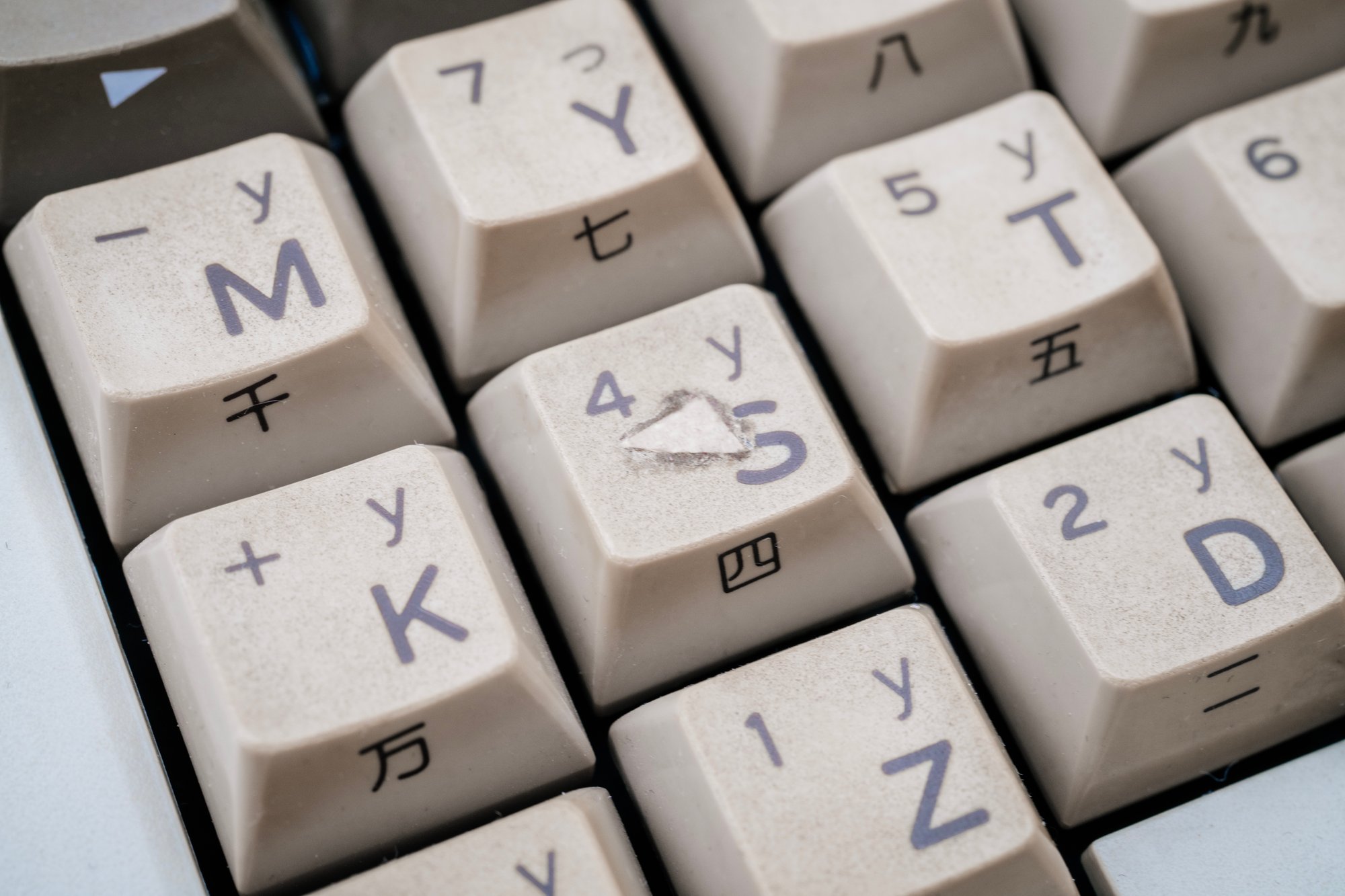

But at least there’s something familiar in the PWP-100 keyboard I imported. When you look closely at two keys, you will notice the owner glued two primitive homing nubs to aid their index fingers.

On the surface, this is not unusual. Many people all around the world did this before; touch typing has been established since the early 20th century.

Except, of course, in Japan. Japanese typewriters were too complex for touch typing, and up until the microcomputer era, many people have only known fast keyboards from pianos and calculators.

In Japan in the 1980s, touch typing was genuinely new. And so, looking at these crude homing stickers makes me strangely happy. It’s not that touch typing is a necessity to deal with keyboards, or that the owner chose a layout that was ultimately a failure. It’s just that Japan, after so many decades, finally got keyboards where one could type as fast as they wanted.

Marcin

In a few days: Another Japanese manufacturer’s take and a tale of peculiar market segmentation

This was newsletter №46 for Shift Happens, a book about keyboards. Read more in the archives