Cover story, pt. 2

As the book is nearing its delivery, please check out the cute mini game I made out of the book’s slipcase.

Also, the book got a nice write-up in Ars Technica and I was on a short and sweet public-radio podcast.

⌘

The booklet cover story was cute and nostalgia-filled. In contrast, designing the rest of the book covers ended up among the hardest design task of the entire project.

I am not a cover design expert. It feels like a very specific universe I barely understand, similar I imagine to movie poster design and album cover design – at the same time hand-in-hand and at odds with the works of art they are meant to represent.

A cover has a functional goal – communicating the author, the title, some accolades, and perhaps the genre – but also an emotional one and a marketing one. It needs, I guess, to attract the eye, standing out just the correct amount and in just the right, hard-to-explain way.

That’s the front cover. The back cover is where the blurbs and quotes go, and the barcode, and the price, and various other little bits of metadata.

But my book felt slightly different than other books on my bookshelves. The Kickstarter approach lessened the pressure for the cover to be noticeable and to sell the book. Likewise, the blurbs, the accolades, and the price already existed online. And I wasn’t even sure I needed a barcode.

Fewer things to do means less worry, right?

Not quite. Now I had more space to fill with something, and that something was poorly defined. On top of that, I had three different surfaces to handle – the wrapround cover of the slipcase, the front and back covers of the volumes, and the endpapers. (Endpapers are the first two pages immediately after you open the hardcover book, and before you close it. In hardcover books, they are printed separately on different stock, and eventually literally glued to the covers.)

⌘

But let’s rewind. It wasn’t always like this. Before the decision to wrap the book in a slipcase, before I split the book into two volumes, and before the book even got its title, I already played with establishing the project’s visual identity. The first attempts, using the original codename Keyboard Secrets, were so laughable I’m sharing them with a huge grimace on my face.

The first okay-ish idea I had for the visual language of the book used stylized keys based on a treatment I saw in one obscure tech book from the 1980s. I designed keys from other eras in that style, and for a little bit I felt good about this.

But then I noticed I got more excited every time I saw something real – or photorealistic, at least – and I decided the book should never show drawings, so the key visuals had to go (you can still see this treatment survive in the old poster store).

I zeroed in on one of the most iconic Shift key shapes: one from the Selectric typewriter, stepped, with shiny surfaces and centered text. (Remember Steve Jobs describing Aqua as lickable? This key was lickable in real life.)

I took some nice close-ups, and even tried to incorporate the book’s new (and final) name in Photoshop. By this time I also knew the book was going to be two volumes (no slipcase yet, though), and I started experimenting with back cover as well in various combinations of black, white, and orange – the book’s primary accent color.

The rest was slowly getting somewhere, I thought. But the Shift Happens key never existed and so bolting on “Happens” always felt gimmicky. Would it feel different if I used a realistic rendering to create that key?

One weekend I fired up Blender and started imagining that scenario.

This looked amateurish still, but I knew that with enough time and effort I could make this feel exactly like the lickable Selectric Shift. And yet, I put it aside quickly, and only months later I understood my hesitation was a sign I already knew I was not happy with this treatment.

⌘

I also had endpapers to deal with. Here I thought I came up with what felt like a perfect idea. Why not grab all of the nice symbols from various keys I recreated and used for footnotes…

…and throw them all on one page in an interesting pattern?

Learning from my previous mistakes, I wrote some Figma scripts to do that, experimented with a few color combinations, and grew to like the results.

⌘

In the meantime, deadlines started detaching themselves from the horizon. At this point, I also made a call to include a slipcase (in part to justify the book’s price point that had to grow because of printing expenses). And so I had three surfaces… but only 1½ ideas.

I explored other approaches for the covers. How about using the iconic Dvorak hands? Or all the keys in the book? Or a photo?

But all of these were bad ideas. The iconic Dvorak hands were cool but ugly. Similarly to the endpapers treatment, which I already started souring on, a dump of keys in the book felt like… a website. And someone told me photos on the cover were a sign of a low quality endeavor. Good books didn’t use photos. Even if the book didn’t use illustrations, the covers had to.

After a lot of soul searching, I arrived at this plan:

1. Keep the endpapers with symbols.

2. For the cover, put together a classic QWERTY staggered layout – but using photos and not renders. (I never finished the Blender explorations, but I got better at taking macro key photos in the meantime.)

3. For the slipcase, use close ups of some of those nicely sculpted keys, dark on dark to feel both luxurious and luscious.

This was the setup just before the original planned Kickstarter date of April 2022. In hindsight, I am so glad that I delayed the release, because I was really unhappy with it still. All of this might have looked minimalistic, and elegant. But it was also really boring.

⌘

I realized that I worked so hard for all of the photos inside the book to participate in telling the story of the keyboard, but all of the exterior surfaces as I designed them did very little of that, and that bothered me. What could I do to change that?

Luckily, just like sometimes happens with design, I already found all the ingredients. I needed only to recombine them.

I loved the dark-on-dark theme. I loved how the slipcase felt it promised something mysterious – the codename for the book was, after all, Keyboard Secrets. I still loved the symbols, too.

So I started looking at other photographs in the book, and I found I kept returning to one in particular: A mysterious photo of a woman with light streaks coming from her fingers:

I liked that this photo was striking and mysterious. It caught attention. The situation (a long-exposure photograph to analyze hand movement) was unusual, the machine (IBM 24 key punch) largely forgotten today. I had this photo as the opener of the chapter about RSI, but maybe it deserved more. Seeing this on the cover, wouldn’t you be interested in opening the book and reading more?

This was also the time I went to Stanford to investigate the unbelievable Laser Eraser, which came with its own striking stock photo:

These were both Keyboard Secrets – both somewhat matched visually, both were in good enough resolution, both contained fascinating stories. This was fun. Who cared that photos on covers were not typically done.

Now, the question was: could I possibly find two more to cover both sides of both volumes?

I know it was only two photos, but this felt daunting. I needed matching style, high quality, available (and not too expensive) licenses. I wanted good stories, and I wanted gender parity.

These were some steep requirements, but I started poking more. It wouldn’t make sense to search for more photos if the two I had weren’t even possible. But they were: the Computer History Museum allowed me to use the light streaks photo, and the license from Getty for the other photo while steep, wasn’t too step.

I threw myself at this challenge. I scoured stock photo sites, and revisited my database. I found many photos that foot the bill, and asked some of friends which ones felt most interesting or mysterious to them:

There were setbacks. There was one photo in particular, one of an actual keyboard designer, I could never locate. I found it in one Spanish magazine from the 1980s. I bet it’s there somewhere deep inside the archives of one of the old computer keyboard manufacturers, but this time around I didn’t have time or energy to pursue it.

Eventually, however, I arrived at these four photos below. They worked as a system. The photos in volume 1 promised answers to typewriter secrets. The photos in volume 2 were about computers, including a photo of a woman operating a host of various IBM devices I talked about in the book.

And the photo of Rolf Hagedorn I once found in a random folder of CERN archives felt like a perfect counterpart to the light streaks photo. The angles and style matched, and here also was a mystery: what was this strange computer with two keyboards?†

It would be great to have it to open the second volume. I wrote CERN about it and they allowed me to use it, but with one caveat: I also needed to clear the model release.

However, the “model” was long gone. Rolf Hagedorn left minimal internet footprint. I learned of no children and no trust. It felt like another blind alley, which was infuriating – the more I looked at it, the more this felt like the perfect photo.

Then, my editor had a brilliant idea: reach out to someone who once made a short biography of Hagedorn to see if he could direct me to the scientist’s estate. I wrote the email without holding too much hope, and went to sleep.

I woke up to a miracle. Not only Hagedorn’s biographer responded, not only he directed me to his daughter whom I didn’t know existed, but by morning the daughter already responded giving me permission to use the photo.

This was perfect. I got my four covers with four mysterious stories. I cleaned them to make them match, I extended them using AI (please hear me out), and I left room for the title in minimalistic varnish.

Now I only had to find a replacement photo for the RSI chapter. This was hard and took many hours, but in the end I found a photograph that was much, much better for that than the woman with the light streaks. (This happened many times before! I thought I was done, a strange limitation forced me to revisit a photo or a layout, I feared that would make the situation worse, but eventually I ended up with something improved as a result.)

⌘

I finally had my covers. Now I had to figure out the slipcase.

By this time, it was four years since my Blender experiments and I forgot about them. The idea of a great photo of a Shift key stuck with me, though, although I already sensed the minimalism of the prior approach wasn’t working.

What if I could have a cake and eat it too: a minimalist treatment of a maximalist idea? After all, it felt silly that I had a labored collage of Enter keys in the book, but no equivalent for Shift, which was right there in the title.

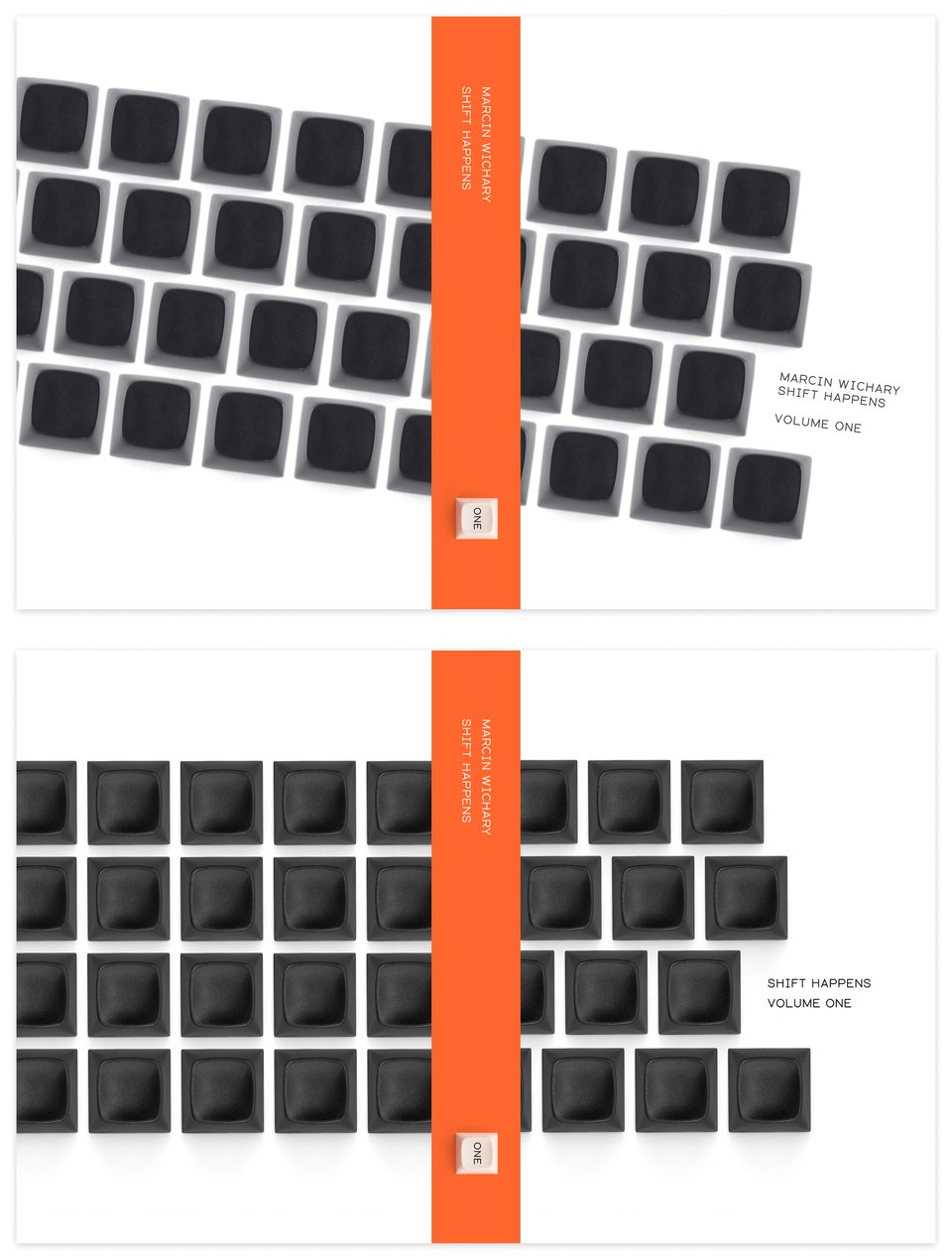

I thought: what if I just take many gorgeous photos of Shift keys on the cover?

Dark on dark was working, so I would limit myself to black Shift keys. Could I have enough of them, covering all the eras of typing, to make it work? Could I take photos that were good enough? Could I assemble them into a nice looking thing?

The first attempts were so bad I almost gave up. But honestly, I had no better idea, so I kept going.

I went through my keyboard collection keypuller in hand, and bought what I didn’t have on eBay: replacement keys for 19th-century typewriters, modern key sets, leftovers from forgotten electrics. I kept photographing and experimenting with lights and reflective surfaces.

The cover files grew gargantuan, to over 10GB – you know you are going deep when Photoshop asks you to switch from PSD to PSB – but at some point I crossed a threshold of quality that got me excited. You could start seeing the differences between different kinds of plastic, and see-through keys were actually see-through.

Arranging all these shapes into a pleasing gestalt was a lot of work, and cleaning all the dirt even more so. But it was coming together.

I originally wanted the various SHIFT labels to be printed in varnish, but it turned out the production issues made decorating the slipcase impossible. So, I decided just to remove the labels for a more minimalistic feel, even though I would miss on great close-up details like this one:

Forty-five keys in, I finally got my slipcase. It felt obvious in hindsight – hey, a book called Shift Happens has photos of Shift keys, right? But the journey there was complicated.

The only part I wasn’t happy with: in contrast to the covers, there was no story here. This was just a random collection of a few dozen keys spanning over a century.

But perhaps just looking nice could be good enough here.

⌘

I said above that I figured out volume covers, but there was one more challenge: the spines.

I knew for a long time that I wanted the spine to be orange, but as the books grew in thickness, the spine shape kept getting more and more problematic to fill. A typical sideways book title felt lost in the space, and orienting it horizontally didn’t quite work either.

I also had to anticipate the just-added third volume, which was much thinner. (The third volume cover was easy, however – instead of going for some sort of a gimmick of me typing on my keyboard, pretending to write a book in a dark room, I decided to just make it a pure minimalistic black.)

And then I had the idea. The symbols from the footnotes and endpapers: what if they belonged here? It would create a hilarious juxtaposition: Shift keys on the slipcase, and symbols from non-Shift keys peaking out from the volumes. A perfect combination, and almost an Easter egg of sorts.

Since the slipcase didn’t allow for varnish or debossing, putting some varnish on the spine would allow it to show even if the book was packaged tightly on the shelf.

I had to talk to the printer about the effective resolution of varnish to make sure I didn’t make the symbols too small. I loved the end result. Typewriter symbols for the first volume, computer symbols for the second one, a mixture of both for the third one.

Bonus: The book in its slipcase wouldn’t have any identifying marks telling you anything. No title, no genre, no price. Just some keys, some symbols, and digits 1 and 2, set in Gorton. It truly felt like Keyboard Secrets.

I avoided having to put an ugly barcode on volume covers, but I was advised to put one on the slipcase. (“Ugly” not because of barcodes themselves, whose aesthetics I like, but because barcodes have to be on a white background to work.) So I did, but I put it… at the bottom, using Gorton font too, in a perfect golden-ratio position partly to recognize design, and partly to make fun of myself as a pretentious designer.

⌘

There was one last piece of this game of chairs.

Using the symbols for the volume spines and for footnotes meant I couldn’t really put them on endpapers anymore – that would be too many symbols.

But I had this idea: the photos I took of the keys were in such high PSB-worthy quality, I could easily blow them up to the side of the entire page. Maybe doing that, and restoring their labels, would be a nice transition from the mysterious universe of the slipcase, to the more real world of the stories inside the book?

I could put them on a violet background – the book’s secondary accent color – and pick eight most important Shift keys, kind of like a guided tour.

⌘

I felt done and happy. I put everything together for the 3D viewer, and only then realized that I forgot to place my own name anywhere. It was meant to go on the volume spines first, but I replaced that with symbols. Then, I thought to put it on the slipcase spine, but I wanted to avoid both the volumes and the slipcase to have a stripe’y look.

Adding that name back to the front cover of each volume was truly the last step. After that, the various surfaces were printed in bits and pieces. We fine-tuned the endpapers when I was on site in Maine in July:

I saw the volume covers, with glorious varnish, in August:

And I haven’t seen the slipcase in person yet – just over a few FaceTime calls.

I’m glad I found time and inspiration to move past the 2022 boring edition…

…and I’m really happy with where we ended up in 2023: the volume covers with four cool stories, the slipcase and endpapers with nice visuals, altogether a package that felt coherent and attractive.

Hope you like it, too.

⌘

It was during the printing of the slipcase that something funny happened.

As I was FaceTiming the team, one of the guys on the floor told me how proud he was of the printing quality that allowed to see the slight texture on one of the keys.

I immediately got excited. “Oh, that’s actually an interesting story! This is from Selectric III from 1980, which they designed specifically so it felt more muted and it wouldn’t reflect the overhead lights in your office, making it harder for you to work. Do you see the other key on the right? That’s the previous Selectric, which was more shiny. Almost something you’d want to lick.”

We then moved on to other topics. But in the evening, I recalled this conversation, and I realized that I needn’t have worried. Even if I didn’t plan for it, the slipcase too was telling stories of keyboard secrets.

Marcin

† Three, if you are actually paying attention!