A to-do list of to-do lists

The dream state of writing a book is the flow state. It’s romantic, this idea that the skies part and perfect words and metaphors and connections flow straight into your fingertips at the pace ideal for measured writing and satisfied reflection.

The good news is that this actually happens. There were moments in the last few years where my brain stumbled upon a phrase I felt so happy about, I had to sit down to a keyboard to write, right then and there.

But this state can also delude. In 2016, I thought of the perfect opening paragraph of my book. I remember where I was exactly: at a dam near Seattle, after visiting the great museums there, among beautiful trees and mountains. It felt like such a writerly, perfect moment, for the first words of the book to arrive this way.

I wrote those words down a few days later. They were crap. In the end, I had to rewrite the opening chapter not once, but twice. (If you buy the book, you will actually get to read both rejected versions in the extra third volume.) I kept that first sentence, out of stubbornness and embarrassment more than anything else, but demoted it to a paragraph somewhere far away from any importance.

⌘

Another state of writing a book is frustration. This one is more common: The off-white pixels of a blank new chapter staring at you. The two parts of the chapter that do not want to fit together. The rewrite never really coalescing.

What helps facing an empty page is a reminder you’ve been there before and survived. What helps with writing and rewriting is the embarrassing notion that you can button mash yourself into greatness. You have no idea how often I kept moving things around and arrived at a perfect flow not through careful thinking, but by brute labour that resulted in a happy accident. Since it happened to me a few times, I now assume that this happens to other writers, too.

This is why I can’t really write on a typewriter. I need my words to be movable, malleable, restless. If quarter of writing exists in my brain before my fingers get involved, half of my writing after that is arrow keys, Shift, and cut high-fiving paste. Those don’t happen towards the end in a mythical, closing “editing phase.” No, these occur immediately, sometimes as soon as the second sentence made an appearance.

⌘

But most of writing my book feels like neither of the above. Most of it is the bureaucratic tedium of to-do lists – perhaps more likely for a book like this, a self-published three-volume monster, where the writing is just a part of a whole production.

Now that the production is nearing its end, I wanted to show you some of those to-do lists.

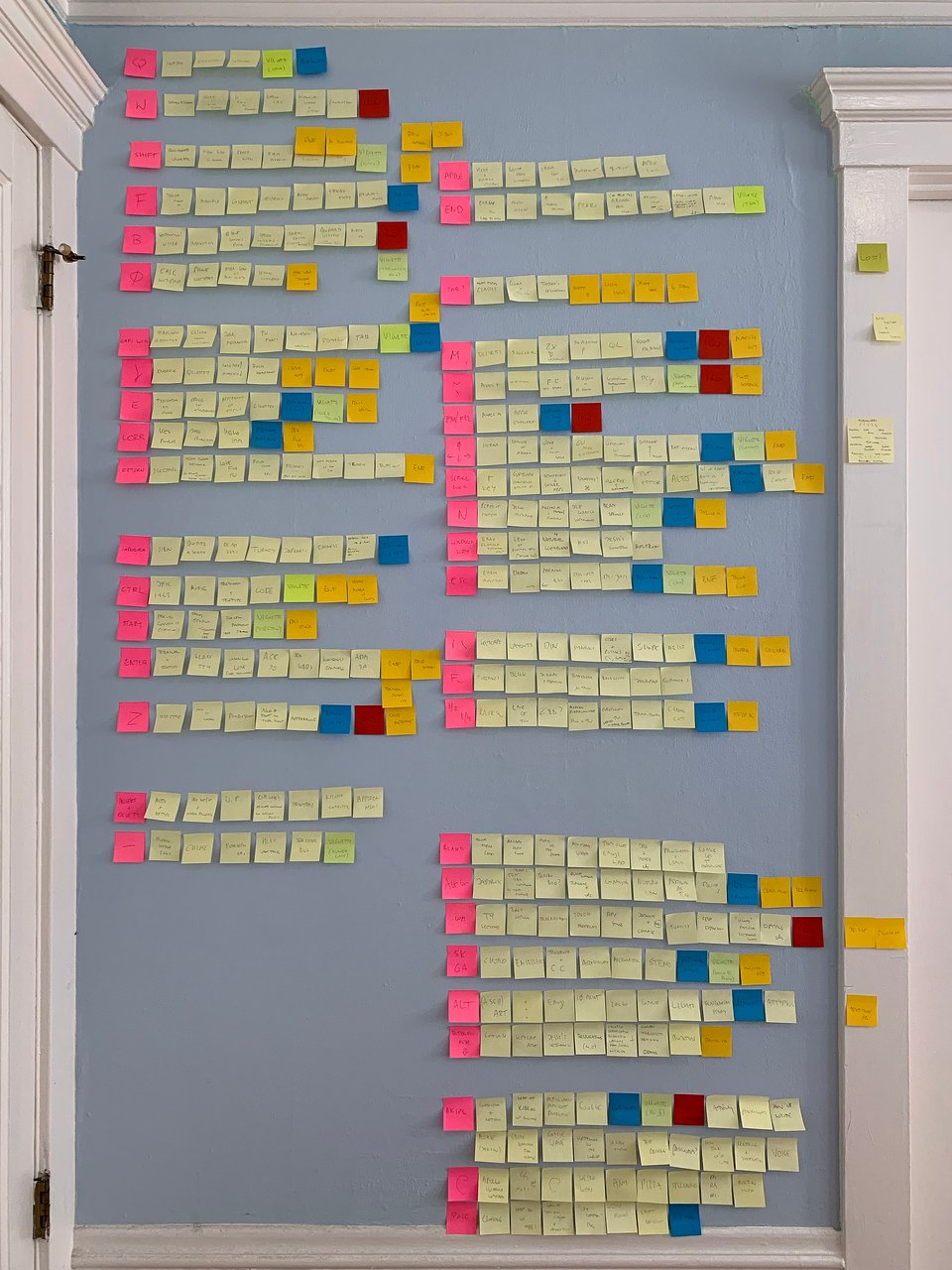

The wall of sticky notes became almost its own character. I stood in front of it for hours, talking to it (sometimes in my head, sometimes out loud). In 2020, it started appearing in the background of my Zoom calls, provoking questions first and sympathy second.

I wrote about it briefly before once or twice, but I don’t know if I shared in this newsletter the simple ritual of progress I grew to love – a chapter written, the photos all done, the editing incorporated – which was replacing a sticky with a new one, even if it said the exact same thing.

Opposite the wall was the book pile on the floor, growing by a week and being categorized into read, reading and to be read up until the last day (go back to an older issue of this newsletter for a small timelapse!)

The other to-do lists were digital.

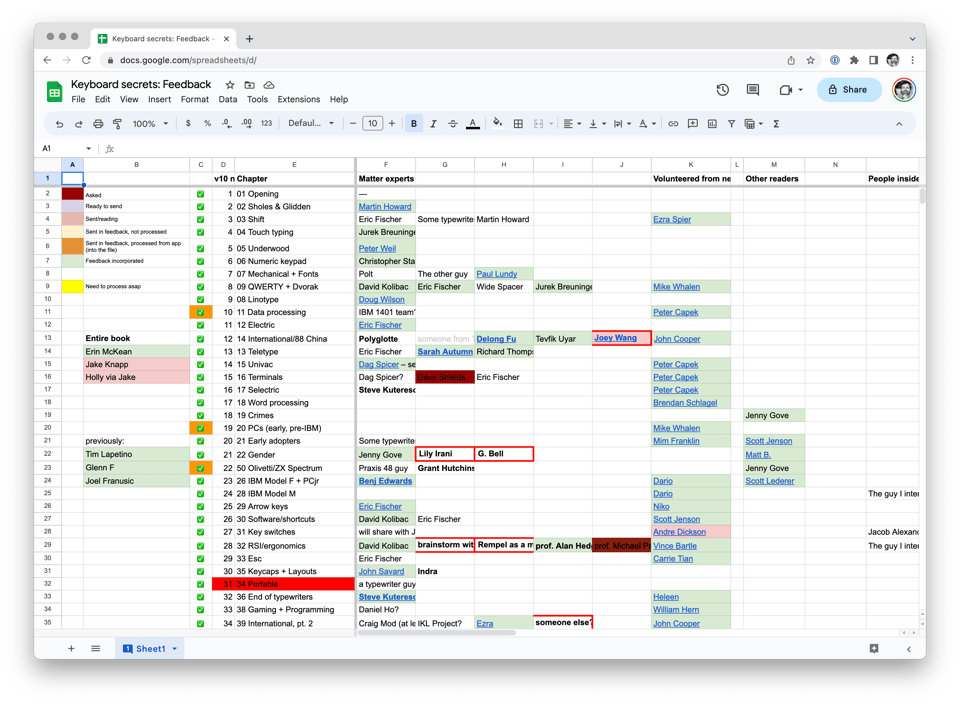

I created a list of readers/reviewers, to make sure I don’t forget a person and that I don’t forget a chapter. I wanted each piece of writing to be read by at least one more person other than the wonderful troika of the editor/proofreader/indexer that kept my writing in check – ideally an expert in a certain domain who could hold me accountable.

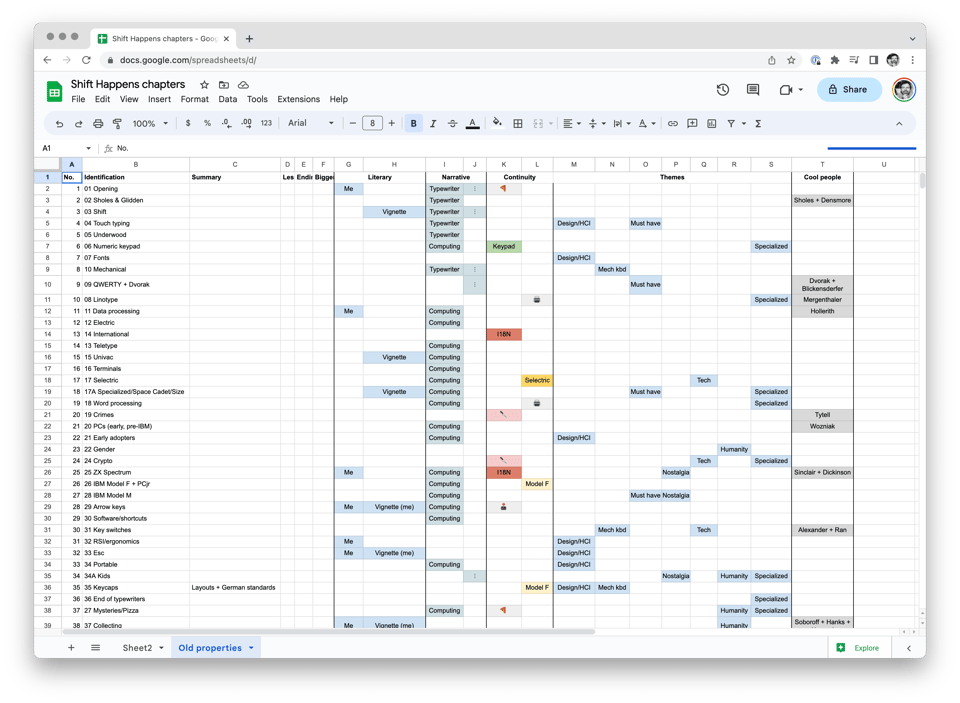

There was also a “narrative” spreadsheet where I tried to make sure the book seemed coherent, especially as the chapters were being moved around and combined. I didn’t quite know what I was doing, but I wanted to see patterns and react to them.

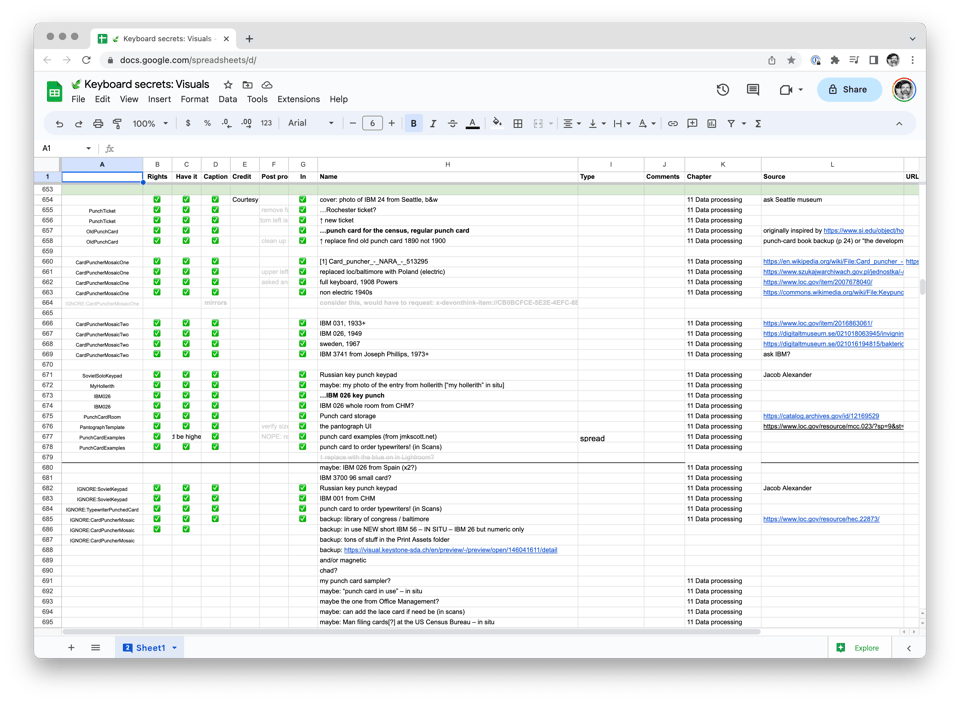

An even larger spreadsheet held the list of photos and visual assets. Here, I kept track of what was available, what affordable, what already inserted in the book, what needed crediting, and what required visual cleanup. I spent a year just in this spreadsheet alone, and visited it often for a few years after that; the list ended up 2,448 rows tall and likely the biggest spreadsheet I ever created without any programmatic assistance.

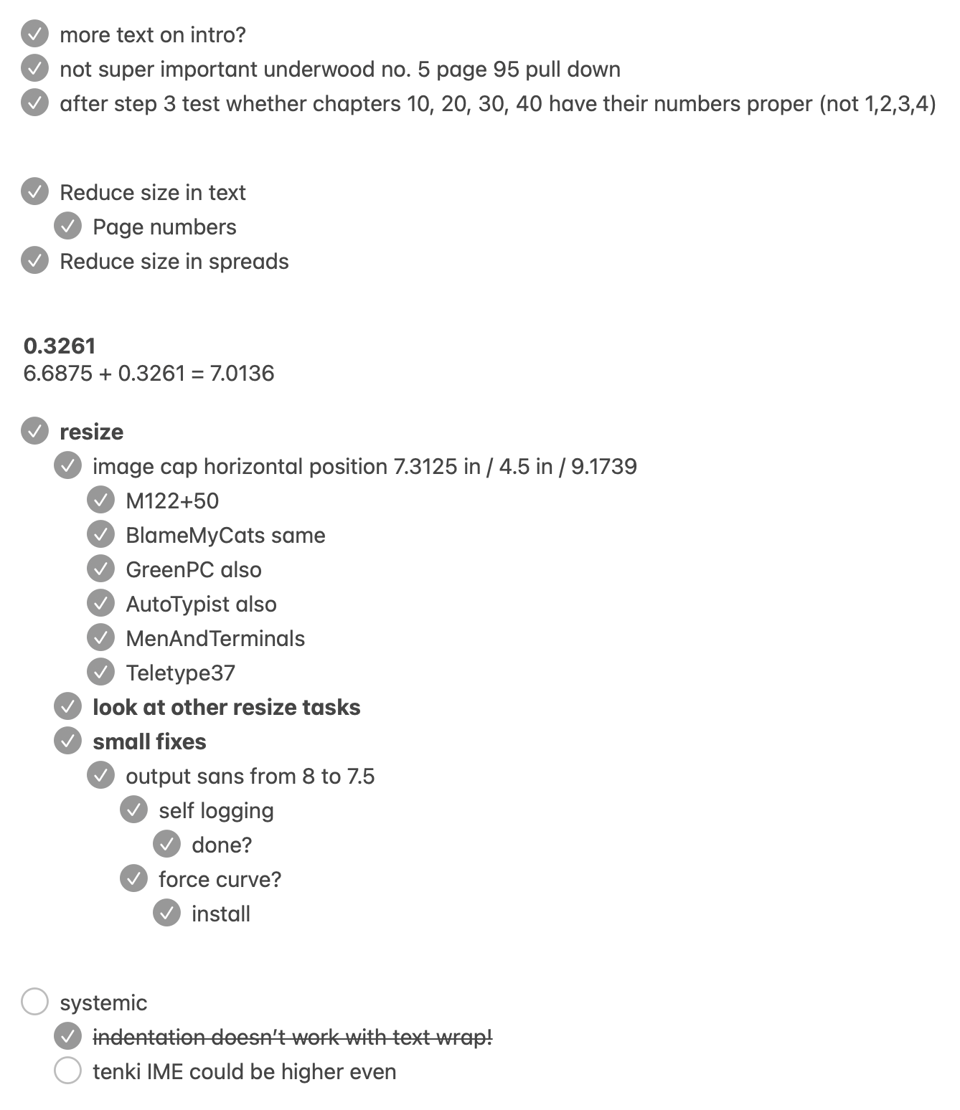

But the most important and largest artifact that kept me going was a simple text list. There were many smaller to-do lists related to specific things: the Kickstarter, the site, the Gorton font. Each individual chapter and each individual newsletter had one, too. There was (still is!) a to-do list of to-do lists. But there was also a main to-do list for the entire book.

Here went everything, from big rewriting decisions to tiny nuances of typesetting. It looked like this…

…except extended into infinity. The sheer amount of unchecked boxes felt overwhelming at times, but if even a hard chapter could be done with sitting down to a page and bleeding – to borrow from the apocryphal saying – surely I had enough blood in me to spare here, too.

Also, I was learning as I was doing. I didn’t start facing… holy shit, 5,400 items (I just counted them all). The new checkboxes kept arriving independent of crossing off the old ones, at times too Zeno’s paradox for my liking, other times trending toward completion.

Plus, I never counted them until now. Scrolling up and down the list it felt like sitting in a train rather than looking down from a plane – watching vistas fly, but never seeing the entire landscape.

It was bureaucracy, perhaps, but it was also comfort. Even a last-minute task had to be written down after completion, partly to feel accomplished, and partly for future bookkeeping (this helped me at least once, when my SSD crashed). Likewise, I over-explained some things as future breadcrumbs, and even wrote down things I deliberately didn’t do.

I used Apple’s Notes to keep track of things. Notes is not a bona fide to-do list manager, but a regular text editor with a strange yellow theme and the to-do functionality awkwardly bolted on. Oh yeah, it was awkward, but just as everywhere else, I loved the malleability and the restlessness: I kept moving things around, writing around to-do items, even inserting an occasional screenshot for reference.

If you want to see it, I uploaded the entire to-do list for my book – 5,400 items, 7,518 lines of text. (I only cleaned it up by removing a few names of people and other sensitive info. Otherwise this is the actual list I’ve been using, although not really in order.)

⌘

I sent the book to the printer at the beginning of May.

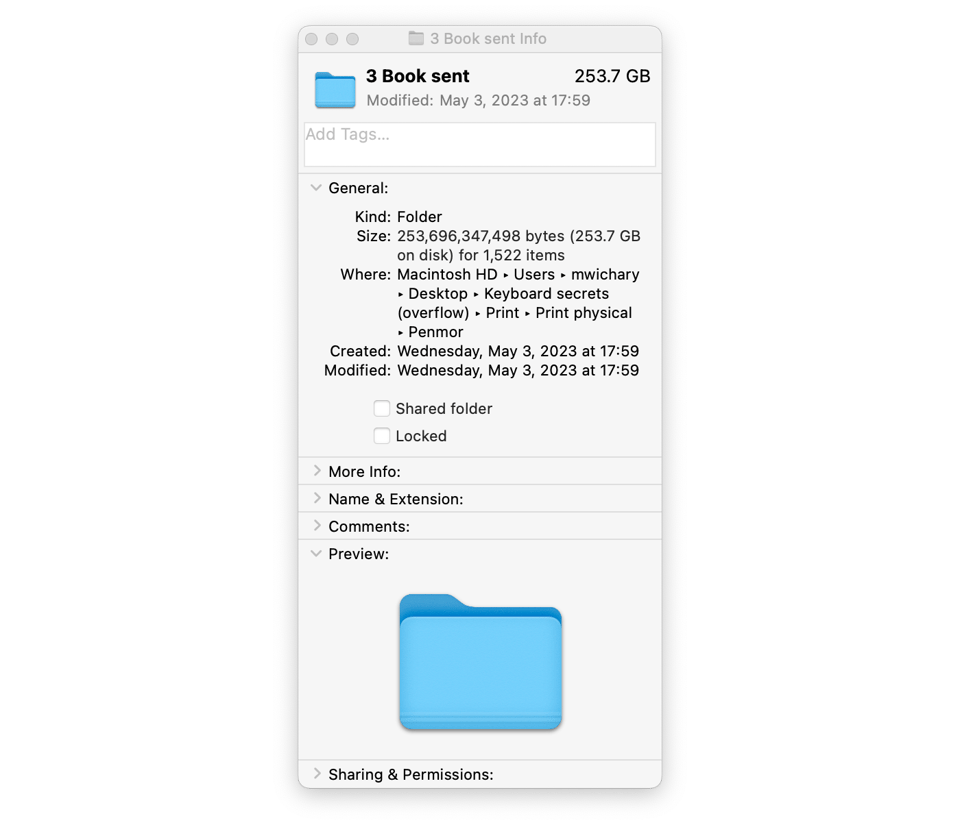

I understand that typically an author is expected to upload the book files internetically, but at over 250GB, Shift Happens was too large for that. Instead, I put it all on an SSD, and secured my bandwidth the old-fashioned way.

The handover happened when I was in New York on a business trip. The Big Apple spared me romance – it was just tedium and frustration. It rained the whole weekend. Over the final days, I kept contorting my body into various shapes as I was crossing off the last checkboxes on the to-do list: in a small airplane, on the hotel bed, on a tiny couch next to it, on a strangely deep chair in a nearby café. There was no tactile pleasure of crumpling a sticky note – just boring trackpad clicks and taps. The clear air of the Pacific Northwest was replaced by personal CO2 meters and KN95 masks.

May’s first Monday morning, I went to the UPS, only to have them reject the address (“we don’t ship to PO boxes”). On the way to the post office, one troubled man threw his cold coffee at me. The post office was itself a small nightmare: a 45-minute wait, a door alarm blaring the whole time, the clerk complaining about my handwriting (do you understand why I love keyboards now?).

But there was no delusion. The book was finished.

There are still other to-do lists. Many of them. I am finalizing the third volume, the booklet, the Gorton font, the index. Despite the main two volumes of the book being “done,” I can and will make tiny changes to it – if only because there is an imminent print test delivery that will likely surface some issues – but those changes will become more uncomfortable and more costly with every passing day that gets me closer to July’s printing deadlines.

Sometime late this year, I’ll be able to archive all of these lists and never touch them again. But I will create one last one, just like I do after every talk, every article, and every other creative project. It will be called “things to try out the next time.” Perhaps even bureaucracy can be romantic. The last to-do list of this project will become the first to-do list for the next one, promising more flow, more frustration, and more magnificence and monotony of thousands of checkboxes.